[_혁신주의] Understanding the Influences on the Human Heart

Obsessive Compulsive Disorder.pdf

400.3K 0 6년전

[pdf보기] LET ME DRAW A PICTURE Understanding the Influenceson the Human Heart BY MICHAEL R. EMLET Introduction How many times have you heard a personyou counsel say something like the following:

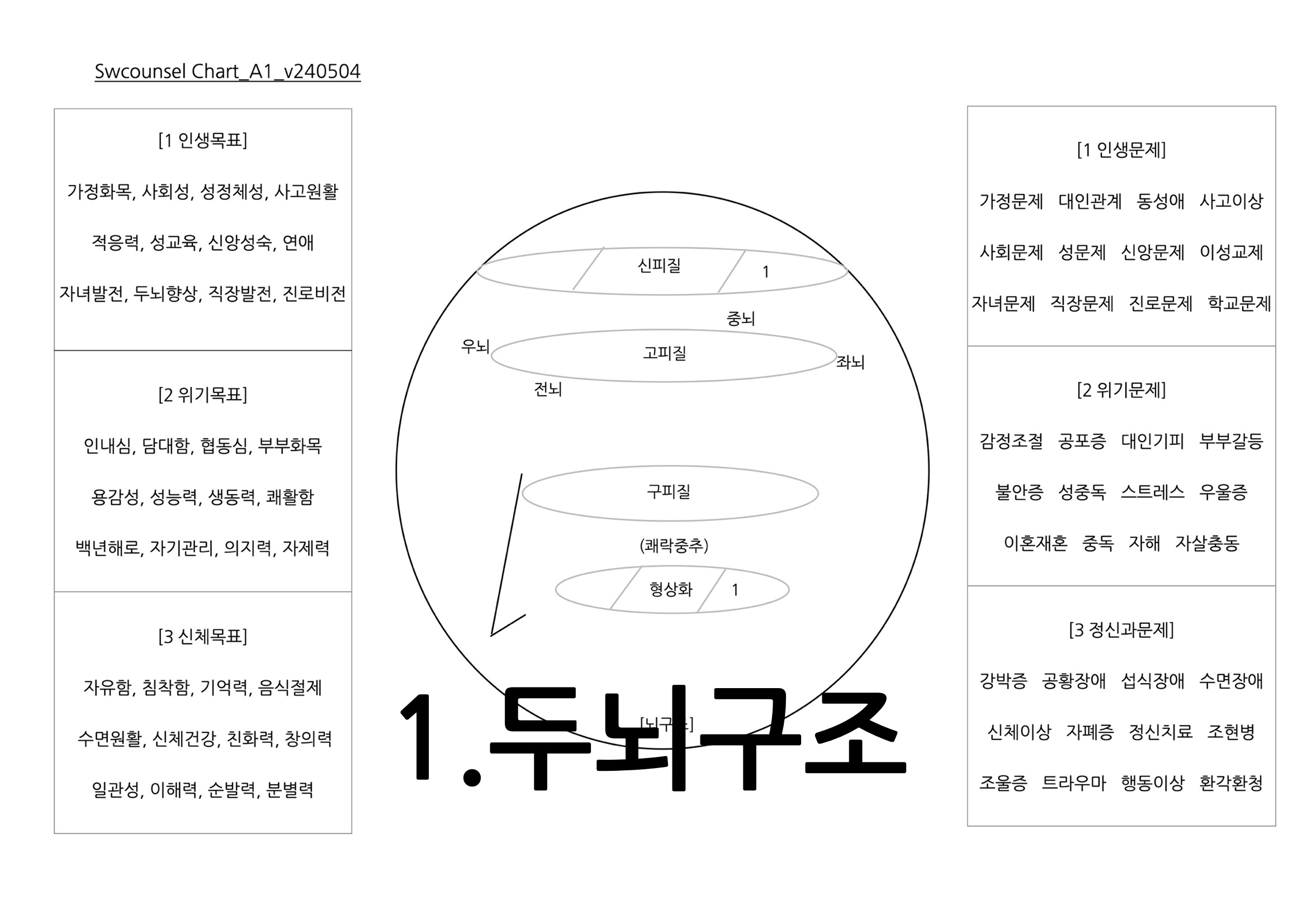

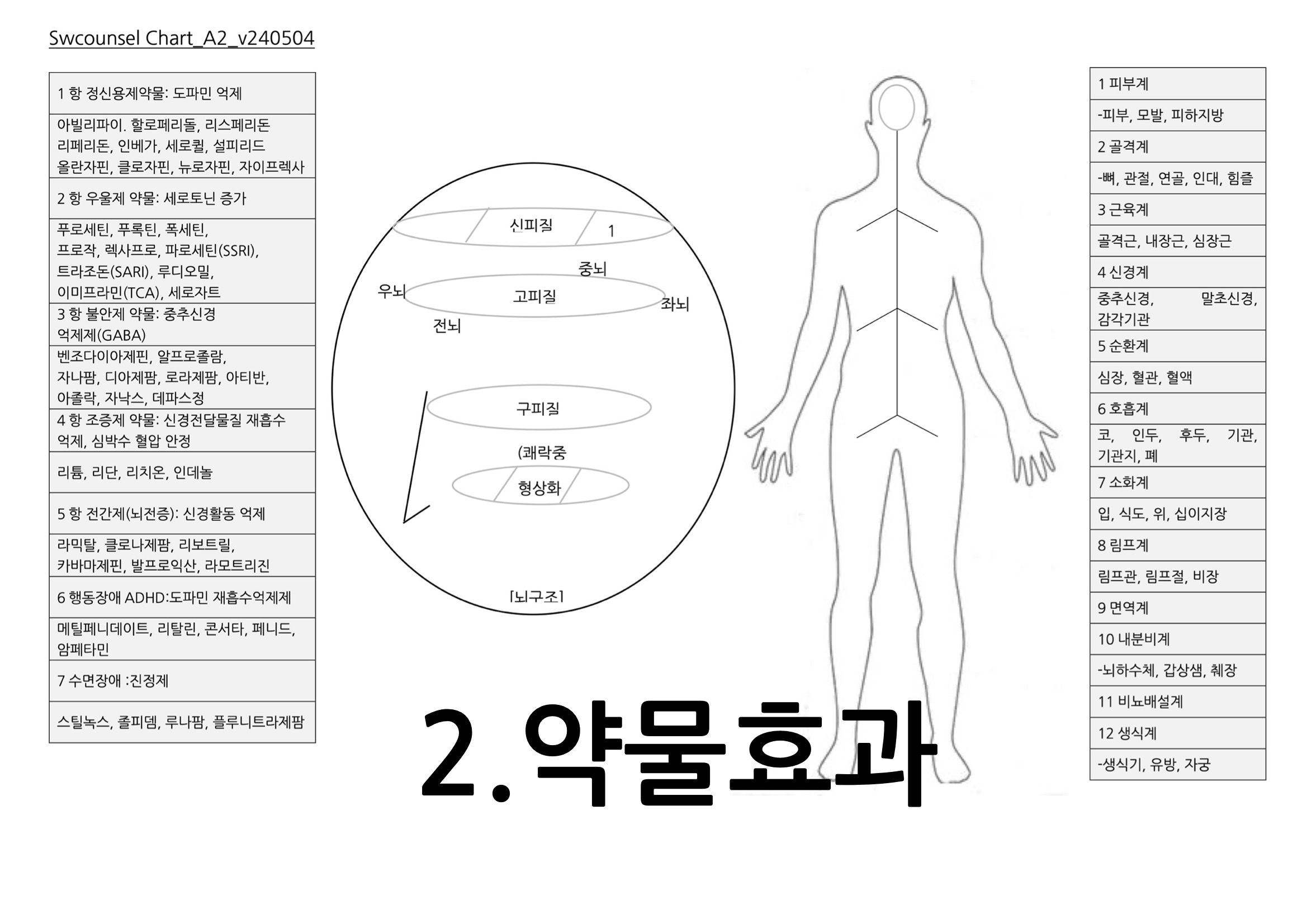

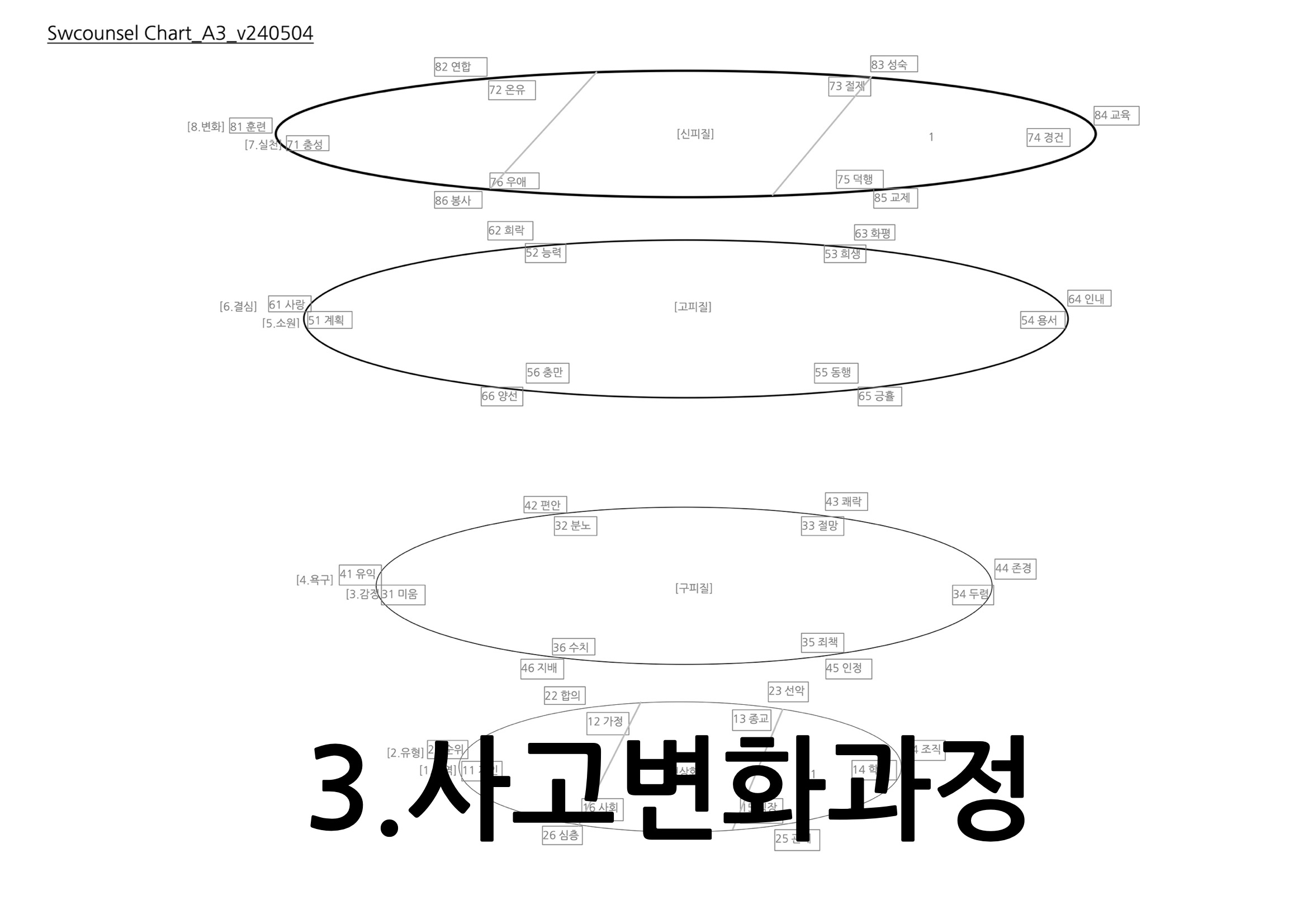

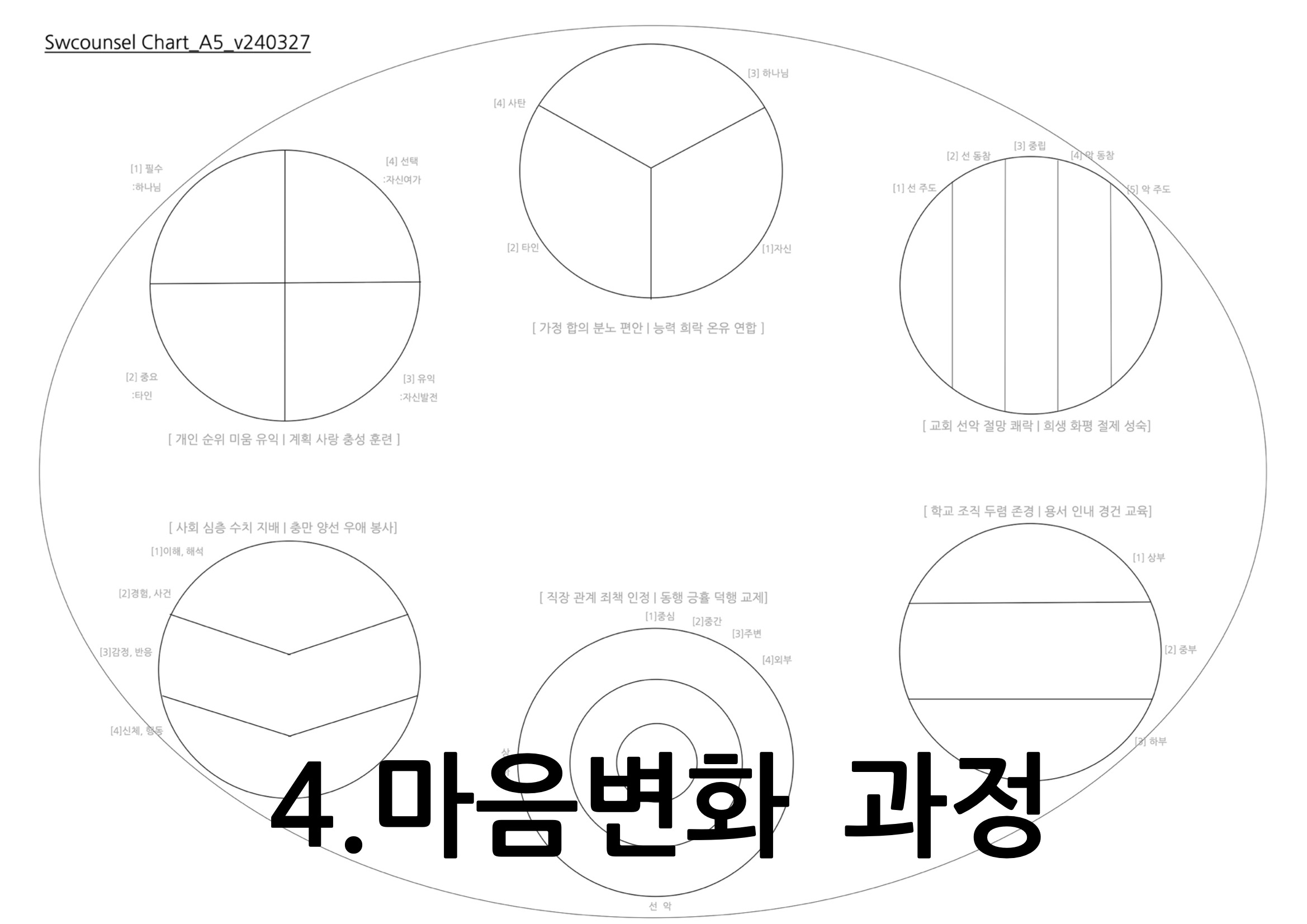

personal, inter-personal, and extra-personal.Put a different way, the influences that shapethe response of the human heart might becharacterized as somatic, relational, and societal-cultural.1 The purpose of this article is todevelop a helpful diagram that seeks to explainthe relationship between the initiating, moralcenter of the person (the heart) and the afore-mentioned three arenas of influence. Hopefullyit will help both counselor and counselee avoidtwo extremes that ultimately short-circuit theprocess of biblical change: either ignoring thecontext in which we live life or concluding thatthe context is determinative of the way we livelife. Either extreme truncates the transforma-tive message of the gospel. How so? Ignoring the influences on us results in afailure to engage with counselees, to incarnatethe love of Christ, and to truly understand thecontext in which beliefs and motivationsbecome expressed. But, on the other hand,concluding that the influences on us determineour actions results in self-justifying, blame-shifting, or a fatalistic lack of hope for change.The following diagram and discussion seek tofind the biblical middle ground between these _______________________________________________ 1From a secular standpoint those three influences mightbe characterized as “nature” (the somatic or physiologicalfactor) and “nurture” (which incorporates the morenarrow relational and the more broad societal-culturalinfluences). The Journal of Biblical Counseling • Winter 2002 47 two extremes. Intra-Personal Influences: The Interaction ofBody with Heart-Soul How do we communicate to our counse-lees the Scriptural truth that human beings arecomposed of two different substances, inextri-cably linked throughout life on earth, material(body) and immaterial (heart or soul)? I oftenstart by drawing the following: being include spirit, soul, mind, will,conscience, hidden self, and inner nature.3Although not exactly synonymous, they greatlyoverlap in their essential meaning, and togethervividly portray the critical importance of theinward disposition of the heart before God. If the heart is the seat of a person’sspiritual-moral life, then thoughts, emotions,and the will to action originate in the heart.That is, from the heart flow cognition,affection, and volition. The heart thinks andremembers;4 the heart feels and experiences;5the heart chooses and acts.6 What the heartinitiates in these three spheres comes to fruitionthrough the mediation of the body. The bodycarries out the heart’s desires. Every thought,emotion, or decision to act will be representedmaterially at a brain/body level. We cannotmove from the heart to the world around uswithout utilizing the body. The relationshipbetween the initiating heart and the mediatingbody can be diagrammed as follows: The biblical view of the person affirms an“inner” and “outer” aspect, which functiontogether as a unity to live before God andothers, either righteously or unrighteously. Onecommon designation that Scripture employs todenote the inner aspect of a human being is theword “heart.” The heart, both in the Old andNew Testaments, refers to the basic innerdisposition of the person who lives either incovenant obedience or in covenant disobedi-ence before God. The term expresses the factthat all human beings at their core areworshipers, either of the Creator or of createdthings, as emphasized in Romans 1. The word“heart” captures the totality of the funda-mentally moral nature of a human being ascreature-before-Creator.2 Other terms that Scripture uses to reflectthe “inner” or covenantal aspect of the human _______________________________________________ 2Cf. Deut. 6:5; Josh. 22:5; 1 Sam. 13:14; 1 Sam. 16:7; 1Chron. 28:9; Ps. 14:1 (and many other psalms); Prov. 4:23;Prov. 27:19; Jer. 24:7; Matt. 5:8; Matt. 6:21. 3Cf. Ezek. 11:19; Matt. 10:28; Col. 1:21; John 7:17; Heb.8:10; Rom. 2:15; 1 Pet. 3:4; 2 Cor. 4:16. _______________________________________________ 4Cf. Gen. 6:5; Deut. 8:5; Prov. 2:10; Eph. 1:18; Eph. 4:18;Heb. 4:12. 5Cf. Gen. 6:6; Lev. 19:17; Prov. 13:12; Prov. 14:13; Prov.24:17. 6Cf. Exod. 25:2; Luke 6:45; Eph. 6:6. 48 The Journal of Biblical Counseling • Winter 2002 It is important to realize that the body isthe context in which the heart functions. Thatcontext may be health or it may be disease (orsomewhere on that spectrum). Hormones maybe balanced or unbalanced. A person may beable or disabled. Either situation demands aresponse of the person as he or she stands beforeGod, and the initiation of this response residesin the heart. This means that while we mayspeak of the heart in moral-covenantal terms —righteous or unrighteous—the body cannot bespoken of in the same terms. As mediator, thebody in and of itself is not the source of sin, butis spoken of in terms such as weakness/strength,limitation, and dependence.7 This discussion isnot meant to suggest an ultimate dualism inwhich one part of us sins or obeys (the heart)while one part of us passively carries out thedesire for sin or obedience (the body). Whenwe sin or obey we do it heart and body. Thematerial and immaterial elements of our beingare absolutely integrated, but it is critical to notethat nowhere does Scripture affirm clearly thatthe bodily aspect of personhood initiates morally.That initiation is the domain of the heart. Ultimately our bodies do not have “thefinal say” when it comes to whether or not welive in faith or idolatry. At most, the body canonly influence our hearts to make that righteousor sinful choice. The Scriptures affirm theactive, responsive-to-God heart, while notignoring the powerful influences of the body onthe heart. These bodily influences range from amissed night’s sleep or the common cold, totraumatic brain injury, paralysis, a cancer-riddled, pain-wracked body or a brain shrivelingin the wake of Alzheimer’s disease—or even abody in robust good health that feels great.These powerful and important influences of thebody, which test the response of the heart,might be demonstrated pictorially as follows: _______________________________________________ 7See Edward T. Welch, Blame it on the Brain?(Phillipsburg, NJ: P&R Publishing, 1998), 40. This entirebook explores the relationship between the heart and thebody and the very practical implications for ministry tothose with definite or possible physiological concerns.This article is an attempt to simply and schematicallyrepresent the foundational anthropological truthsexplored in much greater depth in Part I of Welch’s book. The big question is how will we and ourcounselees respond to the “pressure” that thebody imposes through its weakness, limitation,and dependence (and it may be extremelysignificant)—with obedience or with disobe-dience? We must seek to differentiate between thepressures of the body and the response of theheart in order that we might counsel wisely.We want to call people to obedience andresponsibility to the extent that it is appro-priate, in view of bodily strength and/orweakness. We more easily do this for problemsthat are clearly physical (a fractured bone) orclearly moral-spiritual (fornication). We wouldcall counselees to repentance in the latter, butcertainly would not call a counselee to “repent”of a broken leg!8 Other situations (includingpsychiatric issues) require much wisdom (and acertain appropriate tentativeness) in differenti-ating the role of the body and the role of theheart. This diagram is particularly useful as anorganizing principle for both the counselor andcounselee. Take, for an example, a counselee _______________________________________________ 8Of course, the situation of a broken leg (which in and ofitself is morally “neutral”) can become an occasion for theheart to respond in praise and trust in God’s wise andloving purposes, or it can become an occasion forgrumbling and distrust of God’s goodness. The Journal of Biblical Counseling • Winter 2002 49 who comes to you complaining of recurrent andpersistent concerns regarding the cleanliness ofthe various office tools that he must work withon a daily basis—telephone, copier, faxmachine. He fears they might be contaminated.When he tries to ignore or suppress theseintrusive thoughts, his anxiety increases. Hefinds temporary relief for his anxiety by arepetitive “wiping down” of the office itemswith rubbing alcohol, but the cycle recurs atdifferent points throughout the day. He has lostseveral jobs because of this behavior and is indanger of losing his present position. He haseven been placed on Zoloft by a physician, withonly modest improvement. How should youthink of his problem? Is it a heart issue? Is itbiological? Both? Having the biblical categories of heartand body allows a reinterpretation of data, whichon first glance might be characterized as purelysomatic/biological. In fact, the Diagnostic andStatistical Manual of Mental Disorders might welllabel this counselee with “Obsessive CompulsiveDisorder (OCD).”9 Because such a secular bio-medical model can only “see” the somatic component since it has no category of “heart-soul,” it must assign a biological causation and(usually) mandate a biological cure for thecounselee’s problems. The body-brain is theproblem. The person is a sufferer, yes, but surelynot a sinner. But the Bible is never so reductionistic! Itcompels us to look at both potential bodilyweaknesses and the sin that arises out of theheart. The riches of the gospel apply not togeneric “hearts,” but real flesh and blood peoplestruggling in specific situations with specificheart issues. Robust biblical counseling mustwalk the tightrope of acknowledging realsomatic influences while rejecting any world-view that minimizes the coram deo aspect ofliving, as expressed in obedience to the first andsecond Great Commandments. Put anotherway, faith and repentance never occur in avacuum, but are expressed in the midst of theunique bodily pressures that provoke the heart. After a thorough data-gathering process, a“fleshed-out” diagram that distinguishes betweenheart issues and bodily weakness might looksomething like this: 50 The Journal of Biblical Counseling • Winter 2002 Inter-personal Influences: The Role ofRelationships This same diagram can then be expandedto include relational influences. While thecurrent dominant secular model for explaininghuman behavior is a biological one (“nature”over “nurture”), the role of significantrelationships in defining the person is stillconsidered influential.10 A boy who grows upunder the constant displeasure of a distant,alcoholic father moves from relationship torelationship as an adult, yearning for theaffirmation he never received. An adolescentgirl with controlling, perfectionistic parentswastes away with anorexia. An abused childbecomes an abusing parent. Experience seemsto cry out that other people—their beliefs,words, and actions—shape who we are forbetter or for worse. The Scriptures also affirm the influence ofothers, but without suggesting that these influences(these people) must be determinative of who weturn out to be or how we act in a specificsituation. Other people simply do not have thatkind of power. Nurture, like nature, isconditioned by the heart. Other people cancreate a context that will make obedienceeither easier or more difficult, but they ulti-mately cannot coerce our hearts (us!) to sin.11And that is good news—that we are not heldcaptive to respond sinfully to the sin of others.At the same time, the good news of the gospelof Christ is a great balm to those who are indeedsuffering at the hands of others. The grace andmercy of Christ the Redeemer is as rich,variegated, and deep as the situation of ourcounselees. The better we understand the _______________________________________________ 9American Psychiatric Association, Diagnostic andStatistical Manual of Mental Disorders (Washington, DC:American Psychiatric Association, 2000), 4th ed., textrevision, 456-463. 10See David Powlison, “Biological Psychiatry,” Journal ofBiblical Counseling 17, no. 3 (Spring 1999), 2-8. 11“But each person is tempted when he is lured andenticed by his own desire,” Jas 1:14 (ESV). 12Consider the number of times the Apostle Paul appliesthe truths of the gospel to specific situations ofinterpersonal conflict/relationships in the church (e.g.Rom. 16:17-18; 1 Cor. [especially chapters 3, 5, 6, 12];Gal. 2:11-14; Eph. 4-6; 1 Tim. 3, 5; Philemon). interpersonal pressures in the lives of ourcounselees, the better equipped we will be tominister the truth of the gospel and to speak aword in season.12 Extra-personal Influences: The Role ofSociety and Culture In many ways, this is an extension of thepreceding discussion. The people around ushave a more immediate, direct influence on ourhearts. But the ethos of the surrounding cultureexerts a mediate, perhaps more indirect influence.While this is a subject worthy of a greatlyexpanded discussion, suffice it to say that thegospel is also meant to challenge and redeemthe established norms of the world’s culture,and therefore, it is both wise and loving toassess and understand the societal-culturalfactors that seek to mold our own hearts andthe hearts of our counselees. Calvin describedour hearts as “idol-making factories” andindeed, this would be true even if we werestranded alone on a desert island. But we mustrecognize the influence of the world in aiding inthe construction of these idol-factories. This is a plea to understand the broadersituational challenges in which we and ourcounselees live. The writers of Scripture did notpropagate “generic truth” by distributing it in amass-mailing format to God’s people. Eachbook of the Bible targets a specific audience ina specific situation at a particular point inredemptive history. The truth of the gospel isnot ministered into a relational-socioculturalvacuum, but it is done with an acute awarenessof the multiplicity of challenges that press thehearts of God’s people to respond in eitherobedience or disobedience.13 Similarly, as we _______________________________________________ 13This can be illustrated medically as well. Two patientsmay have the same problem, e.g. high blood pressure,which requires treatment. However, I consider amultiplicity of factors before prescribing a medication—severity of the hypertension, age and ethnicity of thepatient, other concurrent medical conditions, cost andside-effect profiles of the medications, and potentialinteractions with other medications. Similarly, theapproach to the same heart problem in two counselees—e.g. anger—will vary depending on the particularsituations of the counselees. The call to “Be angry and donot sin” (Eph. 4:26) will look different applied to a manwho struggles with road-rage and a woman who suffers theincessant verbal abuse of her husband. The Journal of Biblical Counseling • Winter 2002 51 share the transforming message of the gospelwith our counselees, it must map onto thereality of their life situation, even as thatmessage reinterprets their experience and clearstheir vision to see life with God’s gaze. With this in mind, how might anawareness of both inter-personal and extra-personal influences help us to flesh out theexperience of the previously described counse-lee? Perhaps it would look something like this: Additional specific details can be filled in, justas with the interplay of heart with body. Thissets up the grace and truth of Christ to meet thisperson in these circumstances. Conclusion The preceding diagram is a tool to assist indistinguishing the somatic, relational, andsocietal-cultural influences that face ourcounselees, while maintaining that theseinfluences are not ultimately determinative oftheir responses. This differentiation allows thebreadth, length, height, and depth of the gospelto be riveted to their lives in loving, truthful,wise, and effective ways. Ultimately, we must help our counselees to see the Redeemer whohas gone before us, Jesus Christ, our Great HighPriest and the author and perfecter of our faith.He was tempted in every way and in everycontext—bodily, relationally, socioculturally —as we are, yet was without sin. What thenshould be our response? “Let us then withconfidence draw near to the throne of grace,that we may receive mercy and find grace tohelp in time of need.”14 This availability ofmercy and grace specific for our time of needgives hope to face the multiplicity of influencesthat press upon our lives._______________________________________________14Heb. 4:14-16. 52 The Journal of Biblical Counseling • Winter 2002

|